By Katlin Cilliers | Staff Writer

In December 2017, under the new leadership assigned by President Donald Trump, the Federal Communications Commission voted to repeal net neutrality regulations, casting a shadow on the future of people’s online experiences.

The main idea behind net neutrality is that internet service providers – ISPs – must treat all data on the internet the same. Laws prohibiting ISPs from blocking, throttling or prioritizing online content were passed in 2015, under the Barack Obama administration. This means that certain types of data, such as the one needed for banking, cannot be prioritized – also known as going through “a fast lane” – over pictures or videos, which are more bandwidth-consuming. This way, big corporations, such as Google cannot pay to have their information delivered quicker than a smaller content provider, for instance, a personal blog.

Therefore, repealing net neutrality laws creates a lot of room for ISPs to affect people’s online (and real life) experiences by prioritzing content made by partner companies, while throttling their competitors’. If that happens across the market, the end consumer will end up stuck in the middle of a proxy battle, with a biased and manipulated internet. Giant tech companies have access to data that users can’t even begin to fathom. Now they have yet another layer of control on how people consume information.

How the repeal affects students

One of the key ideas behind net neutrality is that there must be no prioritizing of content, or “fast lanes” for certain types of data traffic. The repeal of those regulations might bring important changes in the way students experience distance education. According to Craig Spurrier, a web designer at KCC, tuition fees might increase if ISPs change the way connection services are delivered on campus.

“If [ISPs] start doing this prioritization model, things could change for Laulima or for distance learning courses,” he said. “ISPs could start requiring the university to pay to be prioritized, and that would trickle down to increasing tuition, for it would come out [of] tuition money, which would directly impact their education. In personal access, students could have to pay to have their Netflix boosted.”

The end of neutrality means that companies like Hawaiian Telcom and Spectrum can determine how content gets to users. If content providers already control what is seen, targeting ads and the like based on information gathered from websites like Facebook and Twitter, now service providers will also have free reign on the speed and actual availability of content, since they will be allowed to block it. However, Spurrier argues that visible changes might take time.

“Realistically, not a whole lot [will change] for now,” he said. “We are not going to start seeing Spectrum blocking stuff, but I think over time, things like services start being faster, if they [content providers] paid ISPs money.”

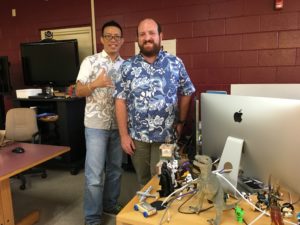

Raphael Lowe (left) and Craig Spurrier (right), Web Developers at KCC (Photo by Katlin Ciliers)

How it affects KCC

Regarding the possibility of new regulations affecting the school’s internet speed, both Spurrier and Raphael Lowe, also a web designer at KCC, reiterate that the university supports net neutrality and, for the time being, there may not be any drastic changes.

“I think we probably will be lucky here, because our two ISPs have been mostly good, so we probably won’t have any direct negative impact, but we could,” Spurrier said.

Basically, the school’s service agreements seem to have an upper hand over those of an individual consumer’s.

“The school’s internet access — the contracts that it is under — are not your standard consumer agreement, so we do have guarantees that have a stronger bargaining position than your regular consumer,” Spurrier said. “Essentially, UH acts more like an ISP rather than a normal customer. We have arrangements with several other groups, so a home or business would just go to Hawaiian Telecom or Spectrum and say, “I want an internet connection” and the ISP would connect them. But because UH is ISP-like, it sets up a variety of deals with other groups to connect the campus more directly. Because of our size and the types of connections we use, we are not limited to just Spectrum and Hawaiian Telecom but rather have the ability to negotiate, theoretically, more favorable agreements. But it still has the potential to be [a challenging situation]”

“Connection on campus won’t probably be affected at all, but our ways of delivering electronic services to students could change”, he summarizes.

Internet services in Hawai’i

Currently, Hawai‘i has two main ISPs: Hawaiian Telcom and Spectrum (formerly Oceanic Time Warner Cable). They are subdivisions within two conglomerates, which absorbed other industries — as it often happens. Carlyle Group owns Hawaiian Telcom, while Spectrum is one of the brands under Charter Communications.

According to Hawai‘i News Now on Dec. 13, both local ISPs have issued notes restating their alignment with net neutrality principles, meaning that they will not throttle, slow or block any lawful content. But so did Comcast on the mainland, and its positioning has changed since April 26, from pledging in favor of net neutrality to the current statement, which reads: “We are for sustainable and legally enforceable net neutrality protections for our customers.” With the end of regulations, there’s no guarantee that the companies are going to keep their pro-neutrality leanings.

“Where [only having two main ISPs on the islands] really ties in to net neutrality is that we have no competition,” Spurrier said.

Having only two main providers gives users little to no option, since there is virtually nowhere else to go. With the end of net neutrality, the already limited ISPs could offer similar packages in case users decide to change their current provider.

Having little to no competition allows ISPs to decide the fate of content distribution. This means that popular content providers, such as Netflix, may face surcharges in order to reach their end customers.

“So, if Hawaiian Telcom or Oceanic decided that we they are now going to surcharge for Netflix, [it] is just those two companies agreeing, and now Netflix is surcharged,” Spurrier said.

Moving forward: what to expect

The equality of internet services is supported by approximately 80 percent of users, according to research conducted by the University of Maryland. However, users and the telcom companies still don’t know the extent to which the repeal net neutrality will affect the public.

It’s all very theoretical at this point because we don’t know if the ISPs are going to change,” Spurrier said. “It was just way more comfortable when they couldn’t.”

That was very insightful. I think we share a vague sense of trepidation, realizing that immediate changes probably won’t be drastic, but that deliberate, incremental shifts could significantly alter the net as we know it.