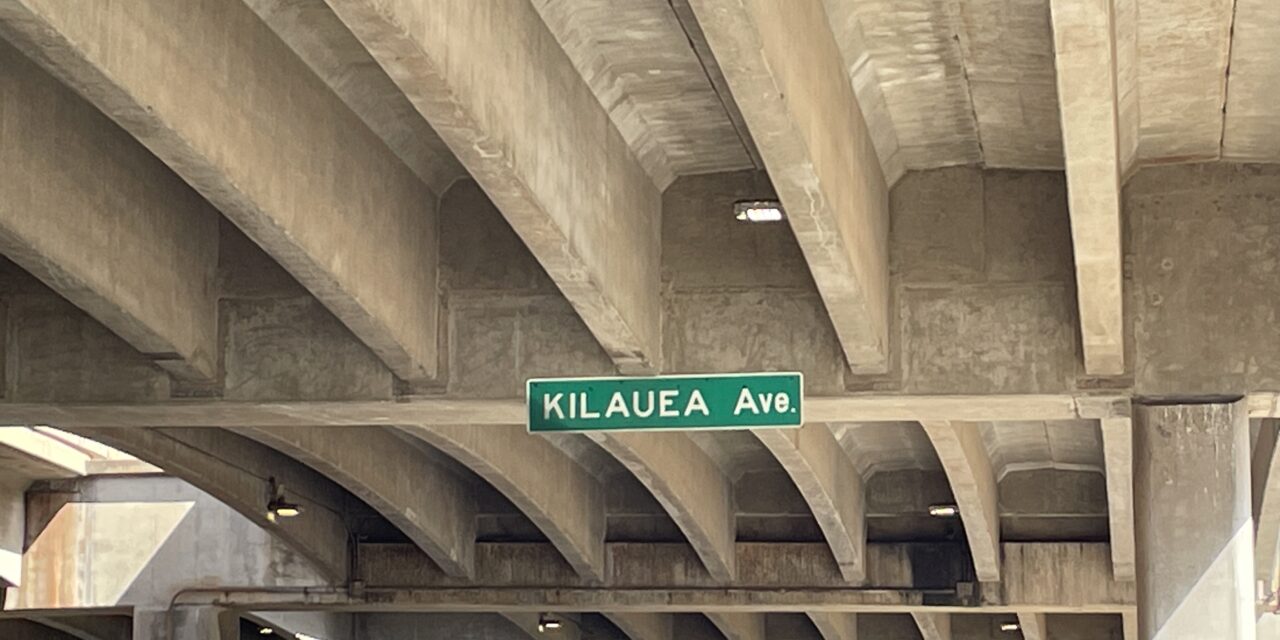

The street sign for Kīlauea Avenue in Kāhala is spelled incorrectly. (Photo by Cameron Enomoto)

By Cameron Enomoto | Staff Writer

Recently, I was at a local business scanning the menu when I noticed that the names of the items in Hawaiian were spelled without the kahakō or ʻokina. Street signs like Waiʻalae Avenue, Moʻomuku Place, Analiʻi Street, and others are spelled without the ʻokina. Even on the Kapiʻolani Community College campus, we have signs that are not spelled properly, like the Olonā building sign, which is spelled “Olona.”

Around Oʻahu, street signs, business names, and license plates in Hawaiian can be found without proper diacritical markings like the kahakō and ʻokina. Diacritics are signs above or below letters that indicate a difference in pronunciation from the same letter when unmarked or marked differently. The kahakō (ā) is a macron and lengthens the sound of the vowel that it is placed over. The ʻokina (ʻ) is a glottal stop that indicates a break between vowels. The word “moʻo” would have an “oh-oh” sound versus being pronounced as “moo.”

It is one thing to be uneducated, but to understand how kahakō and ʻokina are applied and be too lazy to include them where it’s necessary is unacceptable. While the state has made efforts to correct these signs and is currently in the process of fixing misspelled license plates, why weren’t they spelled correctly to begin with?

The beginning of February marked the start of Hawaiian Language Month and news outlets like KITV4 and Maui Now spread the message to Hawaiian speakers and learners that there would be events offered on Oʻahu and Maui to celebrate. While spoken language is crucial in developing speaking and listening skills, what about the importance of written language?

After the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, learning in school through Hawaiian was banned in 1896. As a result, Hawaiian was not used for the next four generations after the ban. It wasn’t until the Hawaiian renaissance in the 1970s that a surge of cultural pride prompted people to continue with cultural practices and sparked significant interest in the revival of the Hawaiian language. Since 1978, Hawaiian has been recognized as an official state language. The fact that it has taken 45 years for the correct spelling of Hawaiian words to be implemented is utterly disappointing.

There are Hawaiian dictionaries online like Nā Puke Wehewehe ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi that allow users to look up Hawaiian words with diacritics to see how the definition changes. For example, the word “mano” can mean either “many,” “shark,” or “dam” depending on if a kahakō is present and where it is placed. Given that Google has thousands of online resources, there is no excuse to leave out proper diacritics when spelling Hawaiian words.

This all just goes to show that people have been complacent in how the written Hawaiian language was incorrectly represented for the past few decades. Hawaiian people as a lāhui have remained steadfast, embraced the ʻike from our kūpuna, and have tremendous pride in the culture and language. Hawaiian Language Month serves as an opportunity for all people to practice, learn something new, and participate in the normalization and perpetuation of the Hawaiian language.