By Katlin Cilliers | Staff Writer

Ask a Professor is a regular feature where Kapiʻo News will highlight the real-life careers and jobs that stem from areas of study at Kapiʻolani Community College.

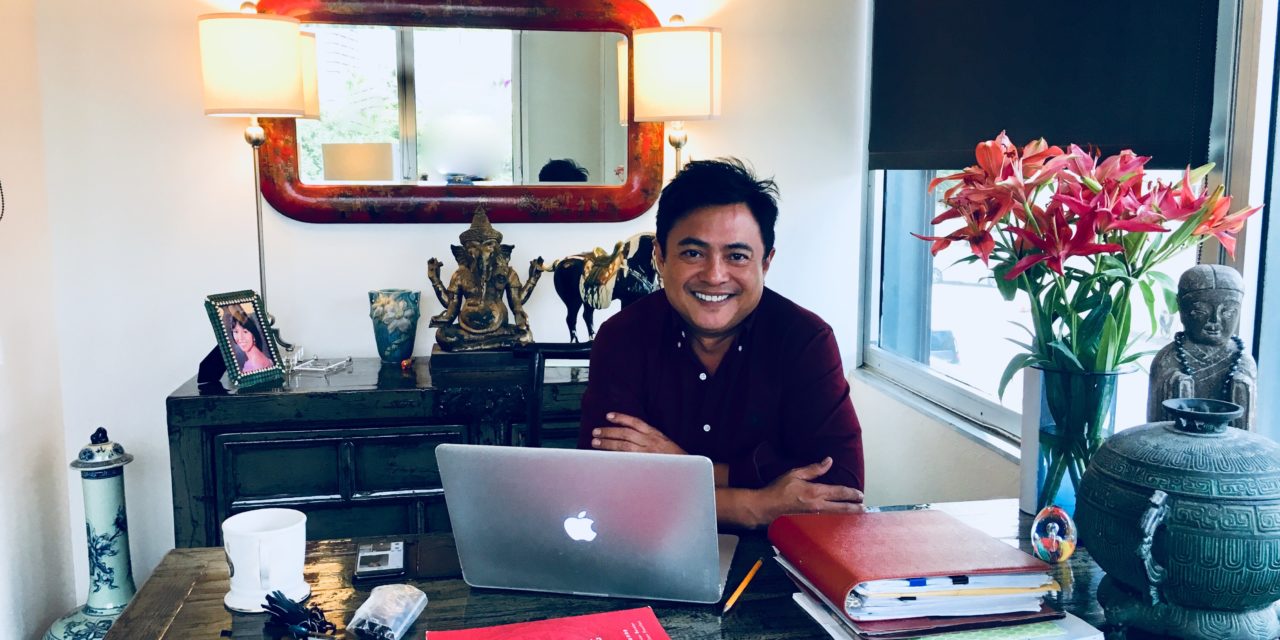

Having a PsyD in Psychology from Argosy University, Dr. Keith Pedro recalls his journey into the field. At age 25, after having taken his MCAT, he dropped his plans of going into pre-med school and went soul-searching in Bali, Indonesia. He claims that the month spent in the country “heightened his senses” and shifted his perspective; he found himself fascinated by human behavior. Upon his return to Honolulu, he informed his father that he wanted to change careers.

Pedro has worked as a forensic psychologist – someone who specializes in legal matters and sheds light on the mental functioning of criminals – for nearly 13 years. He has a private practice in Honolulu and also teaches PSY 100 at KCC.

Do you recall the moment you changed your mind, from medical school to psychology?

During that month in Bali, on a tour to the rice fields, I sat observing this young girl. She was about 7 years old, and she was creating this windmill out of a tin can. I thought to myself, “Someone with so little has so much.” From that point on, something changed. I was fascinated by watching people, and how they interact.

How did your family take the news?

My parents were against it. They wanted medical doctors in the family. We were trying to be the quintessential Asian family. [Upon my decision], I lost my father’s financial support, because he said that if I wanted to go on that path, he wasn’t going to fund my education. I decided to do it even so.

How did you end up involved in forensic psychology?

I overheard someone say, “You get to ride in these police cars, and you evaluate people.” And I thought, “Oh my god, this is so exciting.” I filled out an application that said Department of Public Safety, but I didn’t read it thoroughly. I never thought I was going to be a forensic psychologist. When I got a call from the maximum-security prison, and they said, “We chose your application, could you come down for the processing?” I asked, “The prison? Is there a police station over there?” ‘No.” “I thought I applied for the Department of Public Safety.” “Yes, you did. You are at Halawa, the maximum-security prison.” I was embarrassed to tell people that I’d made a mistake so I just went with it.

What was the job like?

It was a practical rotation, so you had to do 900 hours of assessments, interviews with inmates that were sex offenders. During the first month, I was afraid to be in the prison. But I soon became fascinated by the artwork, their tattoos, the stories behind them. I became engaged with them.

Were you treating them?

I was evaluating them, to help the system decide on the length of their sentence. After so many years of being incarcerated, then [we’d assess] rehabilitation, where they stand sexually, if they are perpetrators. A lot of the exams were very intense. That was [me], training to become a forensic psychologist, but I did it without realizing [it]. In forensic psychology, most of the training is done within that [type of] environment.

Some people would say that dealing with criminals and victims is quite heavy. How do you deal with it?

It is a draining job, but it’s also satisfying. You do need to self-care, to have some down time. I need to not think about work. I never bring home work, unless I must. There are specific days that I say to myself “no more work” and I’ll go home, play the piano and relax.

Can you describe a typical day as a forensic psychologist?

You’d start with checking emails in the morning, making sure of your appointments. Then, you’d go meet with the treatment teams in prison or agency’s offices with case managers. You might have to go [to the agency’s offices] to talk about a case. Forensic psychologists would provide all the background to the case, because the team may not have all the pieces. The murder, the crime, or whatever it was, and based on that, [we’d discuss] how you want them to work with the behaviors, so you’d consult with the treatment team. You might go to court that same day to testify or to observe a court hearing. You would collaborate on planning with the state hospital and other agencies. You work directly with probational officers, judges, hospitals, and case managers. You may be called by prosecutors or defense attorneys to evaluate a defendant or provide psychological assessment.

What is the best part of your job?

The people I work with. You need good support, from your head [of department], the director of health, the forensic chief, my immediate supervisor, the community health administrator. These people have been so supportive.

What is something you don’t like about your job?

When a person dies, and when you hear the victim’s story. Sometimes we feel like we can treat everybody. And we forget that we’re humans.

What traits are needed to thrive as a forensic psychologist? And as a clinical psychologist?

Flexibility in thinking, cultural sensitivity. You must have an open mind. Not be biased, because you cannot go into [a] session and have a bias about something. I work with women in my private practice where they’ve had abortions, for instance. If you’re a therapist who does not agree with abortion, you will have a hard time working with the patient. Be sure that you do not influence the patient with your own personal beliefs. I think you should be continuously educating yourself.

What would you say to a student who wishes to pursue a career in psychology?

Don’t be afraid of all the hard work, or the nights that you don’t get to sleep because you’re studying or reading. Seek constant education. If you have that mentality you’ll do fine. If you have that mentality of “I’ll just do the minimum and that’s it,” you won’t [succeed], because [psychology] should always intrigue us to learn more and more every single day.”

[Editor’s note: To see the Ask a Professor feature on Susan Inouye, a linguistics professor, click here.]