By Katlin Cilliers | Staff Writer

The picture of poverty was clearly painted in Matthew Lum’s description of his volunteering experience in eSwatini, Africa: minuscule, thatched-roof houses in precarious conditions in which families of five or more people must cram into. No toilets as westerners know them; no outhouse. No electric power. Thousands of orphan children either being raised by their sick, elderly grandparents – due to the HIV/AIDS epidemics that has affected families since the mid 1980s – or being left to their own fate.

“Going to an orphanage means giving up not only your land, but also your community, and community is extremely important in rural eSwatini,” Lum wrote in a text in early September.

The 20-year-old has been going to the southeast African country to volunteer and help with his mother’s nonprofit, Advocates for Africa Children, since he was 9. The experience of aiding his mother in her project has been formative in the way he perceives the world around him.

“I don’t know how much I’ve learned that changed the way I thought versus formed the way I thought,” said the Kapiʻolani Community College sophomore.

eSwatini – formerly known as Swaziland – has the highest HIV prevalence rate in the world, according to Avert.org, an HIV and AIDS charity based in Brighton, England. Those high rates make thousands of children orphans every year. The country has a population of a little more than 1 million people.

“It’s a country with about the same land mass and population as Hawaiʻi,” Lum said. “But it’s gotten the highest rate of HIV/AIDS in the world, and also a very large amount of orphan children. … HIV/AIDS is essentially a death sentence.”

AFAC – Advocates for Africa Children – is a Christian nonprofit organization that sends both youth and adult groups to experience the realities of eSwatini, while helping empower the local communities by implementing sustainable sources of living. Their projects include enabling people to raise livestock – as a lot of the rural culture is based on subsistence farming – providing access to potable water through digging wells, and promoting the Christian faith.

“It’s an important part of my mother’s mission that the locals maintain the projects they benefit from,” Lum said, “… that they have a sense of ownership of these projects. [Otherwise], when [volunteer organizations] leave, it falls apart because it is ‘the foreigners’ thing.’”

In a given day, volunteers will chase and slaughter chickens for the group’s own subsistence for the next few meals.

“A lot of people here in America don’t know where their food comes from. … I think it’s generally, like, an eye-opening experience, like I got this chicken. I killed it, and now I’m eating it,” Lum said.

The youth groups also visit schools and interact with local high schoolers in assemblies, receive messages from volunteers and the local pastor, or even from Lum’s mother, Heidi Lum, who is the head of the Hawaiʻi-based organization.

Locals celebrate water faucet installed in the high school grounds. (Photo courtesy by Heidi Lum)

“One of the big things that the team comes away with [after these school visits, is] … these kids are just like us,” Lum said. “They just come from a background of poverty, but they’re like us.’”

In July 2017, one of the youth members from the Hawaiʻi volunteer group noticed how there was no potable water available at the school, and students would often have to miss class in order to go fetch water “at a far distance,” according to Lum. The group decided to take action by fundraising the money to build a well in the school ground. They raised $7,500; the well was drilled in January 2018, and the pump installed in March. Students have had water in the school grounds for seven months now.

In eSwatini communities, laundry is usually the females’ responsibility. So female volunteers are encouraged to join in doing laundry by the riverbanks.

“They’ll use these green bars of soap,” Lum said. “[They’ll] … put [the clothes] in these tubs and I’m not sure whether they use their feet. … We do know that doing laundry that way is hard on the hands.”

Going to a game reserve to see the African animals is also part of the youth group’s experience, as volunteers get to see zebras, impalas – a smaller type of antelope – and giraffes.

During the volunteer trips, KCC student doubles as both a volunteer and aid for the organization. Being from the same age group as the youth guests, Lum gets to join in the activities they do, while also helping his mother to provide a meaningful volunteering experience to the group members.

Lum has also made friends whom he is happy to see when he goes back. One of them is Edward Mkhonta, the pastor at the church in one of the villages. Mkhonta is one of the few middle-aged people that survived his generation’s HIV/AIDS epidemic in the community.

“I’ve spent a great deal of time with him. Whenever I come to the country we greet each other with a big hug,” Lum said.

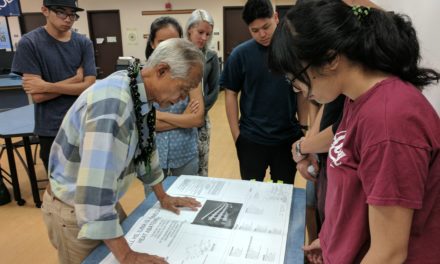

Since middle school, Matthew Lum (left) has been involved in his mother’s missionary work in Africa. (Photo courtesy by Matthew Lum)

Those experiences and connections have helped shape Lum’s perspective of the world beyond his own reality while he still decides whether he wants to pursue a four-year college education.

“One of the things I’ve probably learned from traveling a lot is that you can’t generalize and think of all of Africa as being the same,” he said. “There are several dozen countries there, and each is different; different landscape, different climate, different peoples, different cultures.”

AFAC’s volunteer groups are taken to experience life in the rural communities of eSwatini and Tanzania. They try to get teams to go to Africa twice or three times a year. Travel preparations start about six months prior to the departure dates, and those interested can either pay their own way, or raise money for their expenses, which are tax-deductible. The cost of a two-and-a-half week trip is roughly $4,000.